… there are many means of demobilising the far right. Most striking, though, is the importance of non-state actors: sometimes their actions alone are enough to demobilise far-right campaigns; at other times state intervention is key, but non-state actors often spark and spur on state action.

Over the past year, far-right demonstrations have captured media attention. From several protests against COVID-19-related restrictions to disturbing episodes at national legislatures in Germany and the United States, far-right actors have proven their capability to mobilise on the street. However, these demonstrations, as indeed with many far-right protests, are rarely isolated events. They are part of wider campaigns that use demonstrations and other activities to further strategic objectives. And the quality of inertia is a common characteristic: by acquiring the cachet of ritual and tradition, far-right demonstration campaigns grow stronger as they persist. How then do these campaigns come to an end? How do they demobilise?

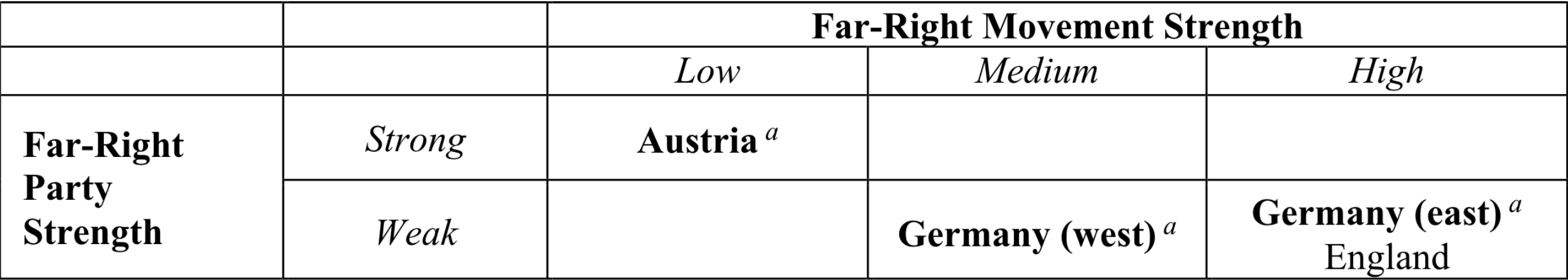

In an article recently published in Mobilization I investigate this question. Looking at large far-right demonstration campaigns in Germany, Austria, and England between 1990 and 2015 offers a useful cross-section of contexts because the strength of far-right movements vary, as do the each each government has that specifically constrain far-right activity.

Country Contexts of Demonstration Campaigns. a The country contexts in bold typeface have specific legal instruments to address far-right activism and demonstrations. Adapted from Minkenberg (2013a: 12).

The quarter-century from 1990 to 2015 also marks an important era for far-right activism. A rising tide of far-right mobilisation followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Particularly notorious is the spike of violence in Germany in the early 1990s. Similarly, the end of 2015 coincided with a shift of far-right activism in Europe. Seismic geopolitical developments–the Brexit vote, the election of Donald Trump – coincided with specific changes to the context surrounding the organised far right: in 2016 the UK banned a far-right group for the first time since World War II and across Europe the emergence of the 2015-2016 refugee crisis heralded a new era of far-right mobilisation. In total, there were 32 large far-right demonstration campaigns active in Germany, Austria, and England between 1990 and 2015.

The study applied qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) techniques and found four patterns that account for far-right demobilisation. Within the study, the most common pattern is marked by civil counter-mobilisation. This includes cases of social movement organisations and other non-state actors working to stop far-right campaigns. Looking at the cases covered in this grouping shows the presence of other conditions that are relevant to the demobilisation outcome. For instance, the second Hess Gedenkmarsch campaign, which occurred in the first half of the 2000s in Germany and honoured the memory of Rudolf Hess, a prominent Nazi leader, demobilised only after a new law criminalised glorification of the Nazi regime. The law was certainly spurred on by civil counter-mobilisation: residents from the location of the campaign (Wunsiedel, Germany) lobbied national politicians to adopt a prohibition ‘against Nazi glorification’ (NS Verherrlichung stoppen). In this way, civil counter-mobilisation can act as a causal trigger, setting various demobilisation processes in motion.

The second pattern represents coercive state repression: arrests and prosecutions, bans and proscription. In flagrant cases of illegal activity or disruption of public order the state may intervene to stop the far right. However, for campaigns that are innocuous enough to avoid state repression–eschewing blatantly fascistic displays and not inciting unrest–state repression is rare; uncommon even in Germany, where its ‘militant democracy’ (wehrhafte Demokratie) is configured to defend against the perils of far-right mobilisation.

Demobilisation pattern

Cases

civil counter-mobilisation

Antikriegstag; Fest der Völker; HoGeSa; Lichtellaeufen Schneeberg; Mourn Lee Rigby; 2. Hess Gedenksmarsch; 2. Waffen-SS commemoration; Heidenau hört zu

Pressefest der Deutsche Stimme; Bad Nenndorf Trauermarschen; Ulrichsberg-Gedenkfeier

militant anti-far-right action

BNP Red, White and Blue festival; Trauermarsch Dresden; Wiener Korporations Ball; 2. Wehrmachsausstellung; Bad Nenndorf Trauermarschen

The third pattern reflects a phenomenon familiar to social movement activists and researchers: closing opportunity. New laws or changes to the surrounding (enabling) context can stop or deter far-right campaigns. In Austria, for example, commemorations in Ulrichsberg used to honour Wehrmacht and SS soldiers with state support. The Austrian army participated in the ceremonies and state subsidies supported transport to the memorial site. But participation shrank dramatically to only a few hundred by 2015, after the state withdrew support and stopped the army from taking part. Notwithstanding the decisiveness of state action, non-state actors were important: the ‘Working Group against the Carinthian Consensus’ (Arbeitskreis gegen den kärntner Konsens) began problematising and counter-protesting the event several years before the national government intervened.

The final pattern covers cases of militant action against the far right. Non-state actors applying coercive measures—physical confrontation and violence, blockading far-right march routes or event venues, etc.—can disrupt and ultimately demobilise far-right campaigns. However, the cases representing this pattern suggest brawling, bashing, and ‘punching a fascist’ is perhaps not the most effective approach. Instead, blockades are a common and evidently powerful tactic. (Indeed, much has been written about this tactic, particularly among German activists opposing far-right groups). Some research suggests that confrontational tactics, whether blockades or more direct coercion, are counterproductive as they confirm the ‘stereotype threat’ of far-right activists. Yet militant anti-fascist activists tend to take a dim view of prospects for persuading far-right activists away from their prejudices. Rather, they assert firmly that far-right organising must be stopped. And, notwithstanding qualms and moral objections about the methods, the militant action pattern suggests that these tactics can stop the far right.

These patterns confirm that there are many means of demobilising the far right. Most striking, though, is the importance of non-state actors: sometimes their actions alone are enough to demobilise far-right campaigns; at other times state intervention is key, but non-state actors often spark and spur on state action. This point is especially relevant in England and Austria where, for different reasons, the state is reluctant to act against far-right demonstrations. But even in Germany, where specific legal instruments exist and political actors are often willing to use them against the far right, non-state action is vital to problematise and resist far-right campaigns. Given the resilience of far-right scenes in these countries and beyond, non-state actors must remain able and ready to counter-mobilise against far-right demonstrations that menace state and society alike.

---title: How to Demobilize the Far Rightdate: 2021-10-29description: "... there are many means of demobilising the far right. Most striking, though, is the importance of non-state actors: sometimes their actions alone are enough to demobilise far-right campaigns; at other times state intervention is key, but non-state actors often spark and spur on state action."image: achtung_nazi.pngtwitter-card: image: "achtung_nazi.png"open-graph: image: "achtung_nazi.png"categories: - demobilisation - far right - counter-mobilisation - Germany---Over the past year, far-right demonstrations have captured media attention. From several protests against COVID-19-related restrictions to disturbing episodes at national legislatures in [Germany](https://usercontent.one/wp/www.radicalrightanalysis.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ORU-Year-in-Review-2020.pdf) and the [United States](https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2021/02/19/the-insurrection-was-a-confederate-resurgence/), far-right actors have proven their capability to mobilise on the street. However, these demonstrations, as indeed with many far-right protests, are rarely isolated events. They are part of wider campaigns that use demonstrations and other activities to further strategic objectives. And the quality of inertia is a common characteristic: by acquiring the cachet of ritual and tradition, far-right demonstration campaigns grow stronger as they persist. How then do these campaigns come to an end? How do they demobilise?In an [article](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354779142_Patterns_Of_Demobilization_A_Qualitative_Comparative_Analysis_QCA_of_Far-Right_Demonstration_Campaigns) recently published in *Mobilization* I investigate this question. Looking at large far-right demonstration campaigns in Germany, Austria, and England between 1990 and 2015 offers a useful cross-section of contexts because the [strength of far-right movements vary](https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14782804.2013.766473), as do the each each government has that specifically constrain far-right activity.The quarter-century from 1990 to 2015 also marks an important era for far-right activism. A rising tide of far-right mobilisation followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Particularly notorious is the [spike of violence in Germany](https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/global-extremes/germany-banning-far-right-groups-enough/) in the early 1990s. Similarly, the end of 2015 coincided with a shift of far-right activism in Europe. Seismic geopolitical developments–the Brexit vote, the election of Donald Trump – coincided with specific changes to the context surrounding the organised far right: in 2016 the UK banned a far-right group for the first time since World War II and across Europe the emergence of the 2015-2016 refugee crisis heralded a new era of far-right mobilisation. In total, there were 32 large far-right demonstration campaigns active in Germany, Austria, and England between 1990 and 2015.```{r}library(reshape2)library(ggplot2)tasks <-c("***Linzer Burschenbundball","Heidenau hört zu","Bad Nenndorf Trauermarschen","AN Antikriegstag","1. Waffen-SS commemoration","JN Sachsentag (Sommerfest)","Tag der deutschen Zukunft","Freital steht auf","*REP Aschermittwochsveranstaltung","EDL rally","Freigeist","**Wien Akademiker Ball","2. Waffen-SS commemoration","Magdeburg Bombing Commemoration","Fest der Völker","***Ulrichsberg-Gedenkfeier","2. Wehrmachsausstellung","Lichtelläufen","Einsiedel sagt Nein zur EAE","Legida","1. Wehrmachtsausstellung","*Mittenwald Gebirgsjäger Pentecost","Mourn Lee Rigby","BNP Red, White and Blue festival","1. Hess Gedenksmarsch","*Wiener Korporations Ball","2. Hess Gedenksmarsch","HoGeSa","Zerstörung der Dresden Trauermarsch","*Deutsche Volksunion Congress","Pressefest der Deutsche Stimme","**PEGIDA Dresden 'Abendspaziergang'")siz <-data.frame(name=factor(tasks, levels = tasks),start.date=as.Date(c("1985-01-01", "2015-08-19", "2006-07-29","2005-09-03", "1990-11-16", "2007-08-04","2009-06-06", "2015-03-06", "1985-01-01","2009-04-13", "2015-10-10", "2013-02-01","2002-11-17", "2005-01-15", "2005-06-11","1985-01-01", "2001-11-24", "2013-10-19","2015-09-23", "2015-01-12", "1997-03-01","1985-01-01", "2013-05-25", "1999-07-01","1988-08-18", "1985-01-01", "2001-08-19","2014-10-26", "2000-02-13", "1987-08-15","2001-09-08", "2014-11-03")),end.date=as.Date(c("2020-01-01", "2015-11-07", "2015-08-01","2013-09-07", "1992-11-15", "2013-06-08","2020-01-01", "2015-06-19", "2005-02-09","2014-08-23", "2015-11-21", "2020-01-01","2007-03-03", "2015-01-16", "2010-09-01","2017-01-01", "2004-03-27", "2014-11-29","2016-06-30", "2015-12-07", "1999-07-10","2010-05-09", "2013-07-20", "2009-08-15","1993-08-14", "2012-01-27", "2004-08-21","2015-10-25", "2013-02-13", "2001-09-29","2012-08-11", "2020-01-01")),Country=c("Austria", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany","Germany", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany", "England","Germany", "Austria", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany","Austria", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany","Germany", "Germany", "England", "England", "Germany","Austria", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany", "Germany","Germany", "Germany") )msiz <-melt(siz, measure.vars =c("start.date", "end.date"))# WITH COLOUR: camp_colour<-ggplot(msiz, aes(value, name, colour = Country))+geom_line(linewidth =2)+xlab(NULL)+ylab(NULL)camp_colour```The study applied qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) techniques and found four patterns that account for far-right demobilisation. Within the study, the most common pattern is marked by *civil counter-mobilisation*. This includes cases of social movement organisations and other non-state actors working to stop far-right campaigns. Looking at the cases covered in this grouping shows the presence of other conditions that are relevant to the demobilisation outcome. For instance, the [second Hess Gedenkmarsch](https://books.google.de/books?hl=en&lr=&id=WDar0BM2t2gC&oi=fnd&pg=PA197&dq=Creating+a+European+(neo-Nazi)+Movement+by+Joint+Political+Action%3F&ots=lNVCoiTgTf&sig=K5Yp4pqGRxgznug62q2hwOHzEqI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Creating%20a%20European%20(neo-Nazi)%20Movement%20by%20Joint%20Political%20Action%3F&f=false) campaign, which occurred in the first half of the 2000s in Germany and honoured the memory of Rudolf Hess, a prominent Nazi leader, demobilised only after a new law criminalised glorification of the Nazi regime. The law was certainly spurred on by civil counter-mobilisation: residents from the location of the campaign (Wunsiedel, Germany) lobbied national politicians to adopt a prohibition ‘against Nazi glorification’ (*NS Verherrlichung stoppen*). In this way, civil counter-mobilisation can act as a causal trigger, setting various demobilisation processes in motion.The second pattern represents *coercive state repression*: arrests and prosecutions, bans and proscription. In flagrant cases of illegal activity or [disruption of public order](https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2021.1889493) the state may intervene to stop the far right. However, for campaigns that are innocuous enough to avoid state repression–eschewing blatantly fascistic displays and not inciting unrest–state repression is rare; uncommon even in Germany, where its ‘militant democracy’ (*wehrhafte Demokratie*) is configured to defend against the perils of far-right mobilisation.| Demobilisation pattern | Cases ||--------------------------|----------------------------------------------|| __civil counter-mobilisation__ | Antikriegstag; Fest der Völker; HoGeSa; Lichtellaeufen Schneeberg; Mourn Lee Rigby; *2. Hess Gedenksmarsch*; *2. Waffen-SS commemoration*; *Heidenau hört zu* || __coercive state repression__ | 1. Hess Gedenksmarsch; Sachsentag (Sommerfest); 1. Waffen-SS commemoration; *Heidenau hört zu*; *2. Hess Gedenksmarsch*; *2. Waffen-SS commemoration* || __closing opportunity__ | Pressefest der Deutsche Stimme; *Bad Nenndorf Trauermarschen*; Ulrichsberg-Gedenkfeier || __militant anti-far-right action__ | BNP Red, White and Blue festival; Trauermarsch Dresden; Wiener Korporations Ball; 2. Wehrmachsausstellung; *Bad Nenndorf Trauermarschen* |The third pattern reflects a phenomenon familiar to social movement activists and researchers: *closing opportunity*. New laws or changes to the surrounding (enabling) context can stop or deter far-right campaigns. In Austria, for example, commemorations in Ulrichsberg used to honour Wehrmacht and SS soldiers with state support. The Austrian army participated in the ceremonies and state subsidies supported transport to the memorial site. But participation shrank dramatically to only a few hundred by 2015, after the state withdrew support and stopped the army from taking part. Notwithstanding the decisiveness of state action, non-state actors were important: the ‘Working Group against the Carinthian Consensus’ (*Arbeitskreis gegen den kärntner Konsens*) began problematising and counter-protesting the event several years before the national government intervened.The final pattern covers cases of *militant action against the far right*. Non-state actors applying coercive measures---physical confrontation and violence, blockading far-right march routes or event venues, etc.---can disrupt and ultimately demobilise far-right campaigns. However, the cases representing this pattern suggest brawling, bashing, and ‘punching a fascist’ is perhaps not the most effective approach. Instead, blockades are a common and evidently powerful tactic. (Indeed, much has been written about this tactic, particularly among German activists opposing far-right groups). Some [research](https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2021/08/19/stereotype-threat-and-the-opponents-of-far-right-demonstrations/) suggests that confrontational tactics, whether blockades or more direct coercion, are counterproductive as they confirm the ‘stereotype threat’ of far-right activists. Yet militant anti-fascist activists tend to take a dim view of prospects for persuading far-right activists away from their prejudices. Rather, they assert firmly that far-right organising must be stopped. And, notwithstanding qualms and moral objections about the methods, the *militant action* pattern suggests that these tactics can stop the far right.These patterns confirm that there are many means of demobilising the far right. Most striking, though, is the importance of non-state actors: sometimes their actions alone are enough to demobilise far-right campaigns; at other times state intervention is key, but non-state actors often spark and spur on state action. This point is especially relevant in England and Austria where, for different reasons, the state is reluctant to act against far-right demonstrations. But even in Germany, where specific legal instruments exist and political actors are often willing to use them against the far right, non-state action is vital to problematise and resist far-right campaigns. Given the resilience of far-right scenes in these countries and beyond, non-state actors must remain able and ready to counter-mobilise against far-right demonstrations that menace state and society alike.******<spanstyle="font-family:Garamond; font-size:0.8em;">Originally published as a blog with the Centre for the Analysis of the Radical Right: <ahref="https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2021/10/29/how-to-demobilize-the-far-right/">https://www.radicalrightanalysis.com/2021/10/29/how-to-demobilize-the-far-right/</a></span>